By Marie-Helene Doumet

Senior Analyst, Directorate for Education and Skills

Knowledge has become the new currency of today’s economy. Digitalisation, technological innovation and globalisation have together made intellectual capital the most important asset in today’s era, and countries have responded by increasing access to higher education like never before.

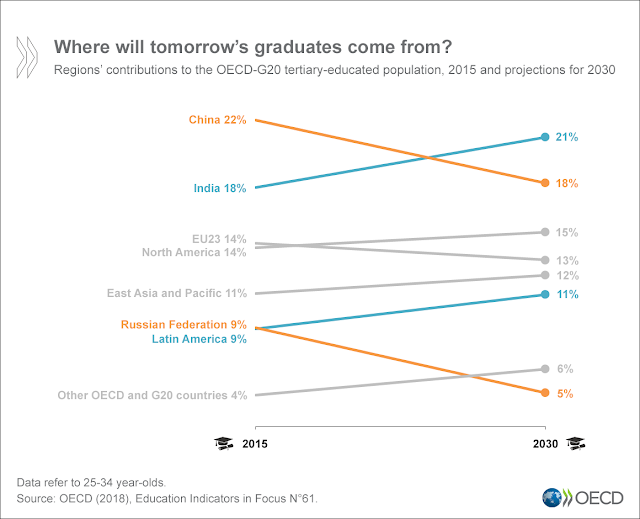

By the end of the 20th century, the United States was the highest supplier of tertiary graduates in the world. Around the same time, the share of 25-34 year-olds holding a higher education degree reached above 40% in only two OECD countries: Canada and Japan. But no one would have disputed back then that the two population giants, China and India, would one day play a major role in supplying the world’s graduates. By 2015, 37 million young adults held a higher education degree in China and 30 million in India. Together, they represent 40% of the total pool of tertiary-educated young adults worldwide, more than the EU and the Americas combined.

And it does not stop there. The latest Education Indicators in Focus shows that despite adverse demographic trends, tertiary education attainment among young adults is set to increase in all regions. Globally, this means there will be 22% more tertiary graduates by 2030.

But, interestingly, the growth will not come from China, whose declining population tends to just about balance out any increase in tertiary attainment. As the figure above shows, it is in fact India, with its rising population and emphasis on education, which is set to surpass China as the largest provider of tertiary graduates in the next decade, supplying the world with more than a fifth of its talent. Latin American countries will also account for a large part of the growth, as tertiary graduates in the region are set to double over the next ten years. Russia, on the other hand, will be facing a decline in its tertiary-educated workforce.

What students study will become paramount to sustain the productive growth of the economy.With such a steep rise in credentials, what students study will become paramount to sustain the productive growth of the economy. Science, technology, engineering, and maths, also known as STEM, have recently been at the forefront of education policy as the backbone of this knowledge economy. Not only are China and India currently the largest contributors to the graduate pool worldwide, but they are also the countries with the highest share of students graduating from a STEM field of study. More than 35% of graduates in China and India hold a degree in a STEM field – more than double the average share from OECD countries. The employment advantage of engineering and information technology, compared to other fields of study, also suggests that supply is yet to meet demand in a number of OECD countries.

Employers on the ground are beginning to feel the impact of this trend. Recent studies have demonstrated that employers are finding it more difficult to recruit the skills they need in their workforce, with engineers and IT scientists among the jobs facing the most shortages. A number of countries have started to look beyond their own borders towards an increasingly mobile international student population in order to fill the gap. Outsourcing software development or engineering work to foreign companies has also become common across a number of sectors.

With the growing number of tertiary graduates, and their increasing willingness to study and work abroad, it is undeniable that competition for talent has intensified. But perhaps a more subtle phenomenon is that the higher supply of graduates is leveling out the playing field of qualifications. In our fast-paced, volatile and uncertain world, a degree on its own is not as much of a predictor of skills as it used to be; what students learn in classrooms today may even become obsolete tomorrow. Those who succeed will be those who have gone beyond the curriculum to cultivate softer skills such as problem solving, creativity, or critical thinking – and, above all, the capacity to adapt, be flexible, and never stop learning.

Read more:

Education Indicators in Focus - No. 61: How is the tertiary-educated population evolving?

No comments:

Post a Comment